Originally written by Nikki Macdonald – Canon Short-form Feature Writer of the Year for Stuff.co.nz | Published on Feb 17, 2018

They’re mostly tiny, boringly black and don’t make honey or live in hives. But they have evolved to pollinate our native plants, and they’re under threat.

Amid endless news stories devoted to the risks of varroa mite and colony collapse to introduced honeybees, native bees have been mostly ignored. That’s ironic, given honeybee numbers are exploding in the mānuka honey goldrush, and those same bees could be pushing out their native cousins.

Around the world, countries are waking up to the plight of native bees, at risk from introduced insects and habitat loss. In September 2016, American authorities took the unprecedented move of listing seven Hawaiian native bee species as endangered, giving them legal protection.

In New Zealand, research is only beginning to investigate the risks to the country’s unique pollinators.

A native Leioproctus bee. New Zealand has 28 species of native bee, which are threatened by the honeybee explosion. Image: Brian Cutting.

Entomologist Barry Donovan has been captivated by bees since helping hive a honeybee swarm that engulfed a tree at his Taumarunui primary school.

He’s identified New Zealand’s 28 native bee species, which largely fall into three families – Leioproctus; Lasioglossum; Hylaeus. See them in your garden and you’ll probably reach for the fly swat – they bear little resemblance to honeybees or bumblebees, either in appearance or behaviour.

Unilke the communal honeybee, the largest native bee family, Leioproctus, is solitary. Females dig 20-30cm tunnels into the ground, into which they lay one egg, and feed the larvae with pollen and nectar foraged from surrounding flowers.

A pollen-dusted native Lasioglossum bee, which could be mistaken for a fly. Image: Jamie Stavert.

Lasioglossum bees are similar, although several females might share a nest hole. The Hylaeus family nests in plant material – beetle holes, or hollow straws in dead flax stems.

While New Zealand’s first honeybee was recorded in Hokianga in 1839, native bees have evolved and adapted over millenniums to suit New Zealand’s unique plants. But while native and introduced bees have very different characteristics, they compete for the same nectar and pollen.

In 1980, Donovan concluded native bees were surviving despite introduced competition. However, it’s hard to measure change without knowing population sizes before honeybees and bumblebees were introduced, he says. And that was before the mānuka honey goldrush sparked an explosion in managed honeybee hives. It’s time to reassess whether native bees are at risk, Donovan says.

“If any organism at all becomes extinct, it’s an unstitching of the ecological web that supports all of us. To lose one bee species would be a tragedy from a human point of view. So we do need to know whether there is an impact – from a purely selfish, survival of the human species view.”

Researcher Ngaire Hart and native bee guru Barry Donovan count bee nests to work out whether native bee numbers are declining. Image: Whangarei Leader.

When Plant and Food Research wanted to know how far genetically modified pollen might travel, Ngaire Hart designed a bee antenna to measure how far the insects flew.

“But when I actually went out in the field to find some native bees, I couldn’t find any.”

That was back in 2004. She spent her next summers – and a Masters and PhD – collecting data at one of the country’s biggest native bee communities in Whangarei. Having developed an imaging system to count nests, she measured population decline of between 27 and 70 per cent at three locations, between 2010 and 2013.

Hart suggested four possible reasons – natural cycles; loss of habitat; environmental pollutants such as herbicides; and increasing competition with exotic bees.

The threat from honeybees is real enough that the Conservation Department commissioned a 2015 review of the risk, by scientist Catherine Beard.

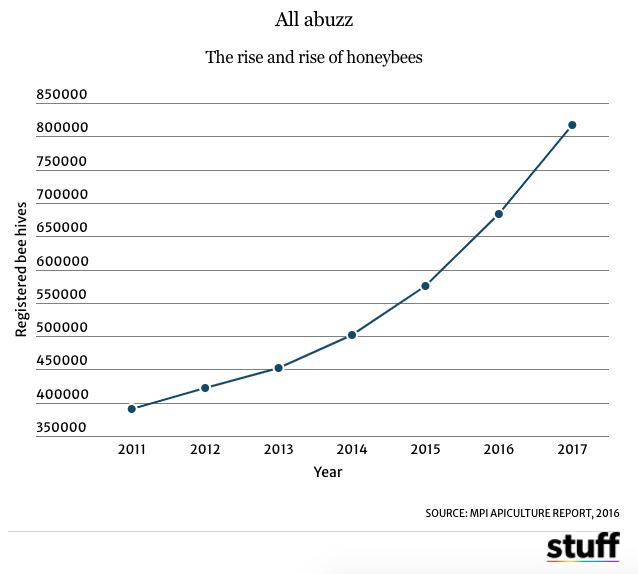

While the arrival of the varroa mite in 2000 wiped out wild honeybee colonies, astronomical prices for mānuka honey has spawned an explosion of managed beehives, from 390,523 in 2011 to 817,483 in 2017.

Honeybees compete with native bees for pollen and nectar.

Beard found hive numbers on conservation land also soared, from 2036 in 1996 to 14,850 in July 2015. She found honeybees collect nectar and pollen from at least 224 indigenous plant species and have a competitive advantage over native bees as they can forage for longer and broadcast food locations to others in the hive.

Honeybees often prefer introduced plants, so can spread weeds, and can take nectar from plants such as kakabeak, without pollinating them, making them less attractive to bird-pollinators such as tui.

“There is also a risk that, for some plants, pollination disruption will result in negative population growth and, ultimately, extinction,” Beard’s report says.

The report prompted DoC to start a tender process to manage further hive applications. However, numbers have continued to grow – the department now estimates 96 concession-holders have around 17,500 hives on conservation land. Another 13 applications are under consideration.

The number of managed honeybee hives in New Zealand has exploded with the mānuka honey goldrush.

Native bees nest in bare, undisturbed soils and need flowers close by to collect pollen to feed their larvae. Now imagine a green paddock with cows traipsing regularly overhead – not an ideal nesting spot, obviously.

Auckland University phD candidate Jamie Stavert studied the impact of farming intensification on New Zealand’s pollinators.

Stavert classified New Zealand’s exotic and native bees and flies based on characteristics affecting how and what they pollinate, and measured their abundance across 12 sites with increasingly intense land use. He found exotic pollinators – which include flies that breed in cow effluent pits – increased in abundance with intensification, by 150 per cent. But only two of 13 native pollinator species increased.

Auckland PhD candidate Jamie Stavert’s research found New Zealand’s native bees don’t like intensive farming practices. One species was completely wiped out as land use intensified.

Some exotic and native species played a similar pollination role, meaning the increase in the exotic species counterbalanced the decline in native insects. But one pollinator category comprised only medium-sized native Leioproctus bees, which were wiped out by greater intensification, meaning any plant evolved to be pollinated by a medium-sized hairy bee could be at risk.

“One of the issues is we don’t actually know what plant species those guys are visiting. That’s a really big hole in pollination research in New Zealand,” Stavert says. “By converting natural habitat into intensive agriculture, we’re really changing the architecture of pollinator communities drastically and we still don’t know what that means, both for the pollination of crops and native plants.”

Why care, if native bees are replaced by exotic flies that do that same job? Ngaire Hart responds: “Would it matter if we lose kauri or kiwi or any other endemic species? I definitely think that things would change, and that we would see it over time. The problem is, we might see it too late. Because once they’re gone, you can’t get them from anywhere else.”